About

Meet the Founder

Louis Ambrosio

President, Senior Advisor

My earliest connection to the stock market dates back to when I was about 4 or 5 years old sitting on my mother’s lap. We were at my dad’s Aunt Frances (Kiki) and her husband uncle Anthony Belfiore’s home. Since these were my dad’s aunt and uncle they were old like my grandparents, and their place in Rego Park, Queens had the old people smell. So there was little for me to do except observe. Uncle Anthony may have had a stroke or some type of palsy since his eye drooped on one side which made his face a little crooked and a little scary for me at the time. But I remember my dad and uncle Anthony talking at the dining room table which seemed like hours. I saw my dad unusually animated and engaged. I figured this must be something important. I asked my mom what they were talking about and she said, “Stocks.” My dad’s step mother would call socks stockings, so it must have something to do with that I thought, stocks-stockings…

Later when we were home, I heard my dad explain to my mom that Anthony told all the aunts to buy Chrysler at $4 and it went to over $100. Now even at that age I knew that was a big deal. I learned later on that Anthony worked at Chase Manhattan Bank in their research department. Again, I was thinking like a laboratory with white mice and men in lab coats. Later I would understand it was reviewing annual reports and SEC filings of companies, more like working in a library.

Years later I remember my dad checking the stock tables in the NY Times. He would look at the prices for At&t and Campbell Soup. These were a couple of stocks that he owned and still owns today. I noticed TV ads for MCI and began following that company’s price in the NY Times. While I never bought the stock, it did have a nice run. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MCI_Communications

In junior high school I was painfully shy and painfully thin. While I was always tall, I wasn’t accepted into the click of kids that played basketball in the schoolyard during lunch break. Same with gym, but I did make friends with another kid David G. David was overweight and not at all athletic. So during gym we would do the minimum circuit and the gym teacher would leave us be. David was quite the raconteur. He would regale me with stories about fast cars and street racing. He would explain in detail how these cars were modified and consumed huge amounts of gasoline. He so engaged me that I walked to the candy store after school and bought “Popular Hot Rodding” and “Hot Rod” magazines and began a new passion. Over the next few years I would immerse myself in anything to do with muscle cars and drag racing. Despite my age, the older teens with drivers licenses accepted me since I knew as much or more about modifying cars for racing than they did.

Eventually my buddy Randy S. helped get me a job at the local Mobil station pumping gas and eventually fixing flats and changing oil. I continued with my passion for cars through high school and into college. When I started at Queens College, I selected accounting as my major only because my mother had read that it was a good career to go into according to the NY Times. I went to college but my passion remained at the Mobil station and eventually I heard one of the owners planned to open a second shop in Smithtown, Long Island. At 20 years old I inquired about buying into the new business since I had a small insurance settlement from an auto accident the prior year. My parents were not happy when I dropped out of Queens College to pursue my dream of owning my own auto repair shop.

I went on to study and get my ASE certifications in engine repair, air conditioning and heating, brakes and chassis and auto electrical systems. Initially the business seemed to be going strong, our shop revenues were rising each of the first 3 months and we were selling a reasonable amount of gasoline. I would read the Wall Street Journal at the counter of the coffee shop while eating my breakfast each morning. During this time one of my customers, Ed P. mentioned that he worked at Bache & Co as a stock broker. I told him of my interest in stocks and asked how much money I needed to open an account.

Ed was kind enough to let me open an account and trade with Bach. I remember going to his office and he shared a quote machine that pivoted between him and a colleague that sat in the adjacent cubicle. Bache was soon acquired by Prudential insurance and I continued to trade with Ed learning a few things about the market and stockbrokers. Ed provided me with some stock ideas generated from their research department. They never worked out. Also, it didn’t seem to matter that Ed’s advice wasn’t very good on investing, you just had to be a good salesman. I do remember that he had a picture of actor Peter Falk on the wall, and once while I was sitting there he entered an order for IBM for Mr. Falk’s account. I remember buying 100 shares of Digital Equipment for my account because they had a spot on PBS’ Nightly Business Report stating they were the second largest computer company.

But the bit of advice that Ed did provide was priceless. He suggested I didn’t fit in with the other guys at the repair shop. He said, “You like this stuff, why don’t you go back to school and become a stockbroker trainee? You could make $19,000 a year.” It hadn’t occurred to me that I could ever be a stockbroker. I didn’t even think it was possible to return to Queens College since I left barely a C student.

At this point I didn’t have much confidence in making this move. I conferred with my best friend Marion C. who was two years my junior but a current Queens College student. She encouraged me to reenroll at Queens and suggested I switch majors to Communications Arts and Sciences since it wasn’t dry like accounting.

Queens accepted me back but I was on probation. Magically, this sub C student became a straight A student on the deans list for my remaining semesters. Upon graduation in May of 1985, I was ready to begin my career in Wall Street. I went on a number of interviews mostly at bucket shops and I was very disappointed. This didn’t seem like an ethical way to make a living. Soon afterwards, my dad gets a solicitation from a High School buddy, Tom Coyne. Tom had just opened a new brokerage firm, “First Long Island Securities” in Carle Place, Long Island. Tom was asking if my dad would open an account with his new firm. My dad said. “No, but my son just graduated college and he wants to become a stockbroker. Would you train him?” Tom eagerly accepted my dad’s offer. First Long Island Securities trained me and I passed the 6 hour series 7 and one hour series 63 examination on my first attempt.

With my newly minted securities license I was ready to break into the exciting world of Wall Street. Tom handed me a yellow pages (phone book) and said to call local businesses and offer Ginnie Mae securities. GNMA (government national mortgage association) bonds were mortgage pass through securities guaranteed by GNMA which had an implied guarantee by the U.S. government. These were long term investments but the credit quality was excellent and at the time they were paying 9% interest. After making hundreds of cold calls over several months I realized that people either had no money to invest, or if they did, they already had a broker and if they didn’t have a broker, they weren’t going to do business with someone who just solicited them over the phone.

Of course there were friends and family members to solicit. I was eager to assist Marion’s dad Bill with his 401k rollover after he was retiring from Sears. Dominick "Bill" C. retired from his warehouse manager position after 45 years of loyal service at Sears. At the time of his retirement, he had a salary of about $35,000 a year. His rollover was approximately $150,000 of that, about $100,000 was in Sears, Roebuck stock and $50,000 in cash. When he received the funds and shares we rolled them into an IRA account with Herzog, Heine, Geduld, who was First Long Island’s custodian and clearing broker. I knew exactly what to do with the cash, a 9% Ginnie Mae security would fit the bill. Bill’s wife Marion Sr. was working at the local school, so between her income and Bill’s accumulated vacation days, severance pay and social security, they didn’t need to begin drawing on the IRA until Bill turned 70 1/2. At the time, Bill and Marion wanted to hold onto the Sears shares. By the mid 1990’s Sears had spun off Dean Witter Discover and Allstate Insurance to Sears Shareholders as two separate companies. In 1996 The Motley Fool became a popular content provider on AOL and promoted the “Dogs of the Dow” investment strategy. The Motley Fool had a twist on the original buy the top 10 dividend yield Dow stocks and rebalance every 12 months, discussed in their book, The Motley Fool Investment Guide. I approached the Conti’s with this strategy figuring divesting a concentration in Sears into some of the other high dividend dow jones industrial stocks made sense. We ended up adding stocks like General Electric, Exxon, Chevron, 3M, Chase Manhattan, At&t, etc.

Friends and Family is a relatively short list of potential clients. Tom Coyne came up with a capital idea to drive new business.. Since we were a newer firm and were very flexible, why not create a relationship with centers of influence? And in New York, Income Tax professionals, CPA’s and Tax Preparers were trusted by their clients to give impartial advice. Tom’s idea was to get the referral from the tax professional and split the commission 3 ways. First Long Island Securities would get 1/3, the tax professional would get 1/3 and the broker would get 1/3. The broker would solicit the tax professional and convince them to sit for the training and taking of the less rigorous series 6 exam that would permit sharing of mutual fund commissions. I was excited about this new idea and put it into action. Over time I was able to get 5 tax professionals licensed and after making less than $5k in commissions in year one, I made almost $25,000 in year two.

One of the accountants that I was able to get licensed was Lou V. He had a thriving tax preparation practice adjacent to the municipal parking lot in downtown Flushing, a block from the #7 subway line. He introduced me to one of his client’s Susan S. who was looking for higher rates of return than what the banks were paying in interest at the time. Susan lived in a studio apartment in a high rise building. She was a widow of German Jewish ancestry. Her accent was noticeable and her posture and appearance was always impeccable. We discussed her investments, and her income. She was entitled to both German and U.S. Social Security benefits. Part of her income was from bank interest on deposits, and some from a modest stock portfolio. There was one outsized position, however, and that was Exxon. I asked when she had bought the Exxon and how much she invested. Susan said she and her husband bought it in 1960, and invested $2,000 for 50 shares. In 1986, the Exxon was worth $36,000.

When the 1987 Stock Market Crash occurred in October, the tax professionals had second thoughts about referring clients for investments. They weren’t making enough money in sharing commissions that they fielding phone calls from tax clients who experienced a significant account drawdown. So by 1988, business was off. I was frustrated and needed to get into a position more stable where I could build a career.

My dad had given me important advice. “Make as many contacts as you can in business. It’s all about who you know.” And, “Find a position at a large company, once you are in you can move around.” I found a position advertised in the NY Times by Chase Manhattan Bank, looking for Personal Bankers. It was a phone based sales position where the banker would befriend and serve existing Chase clients and try to expand their banking relationship.

This was a great way to meet successful customers on Long Island. I also became friendly with my co-workers, many of which I have relationships nearly 30 years later. After Personal Banking, I was offered an opportunity to call on small businesses in the Flushing, Queens neighborhood I grew up in. I learned about small and middle market lending and began to meet business owners that would be ideal investment clients later in my career. I was also exposed to a new group of Chase employees, branch managers and commercial loan officers.

Meanwhile, by 1991 I was yearning to get back into the investment business. I read about a new business that Chase Manhattan launched in Dallas, Texas, co-located with their very successful PFS (Personal Financial Services) offices that underwrote jumbo residential mortgages. Chase created Chase Manhattan Investment Services (CMIS) to sell fee only portfolio management services to their PFS mortgage clients. The clients were just approved for a large mortgage so it was an ideal time to solicit their customer to move their investment business over to Chase. CMIS offices were opened in affluent locations around the country, but not in NY until 1994. Interestingly, the Chase Manhattan brand had more cache the further away from Manhattan you were.

I decided that CMIS was the place for me. I began lobbying my friends at Chase who had some influence with upper management. I wanted the position, but at the time CMIS had been hiring wirehouse brokers with a book of business they could transfer over the CMIS. In return, CMIS would refer bank customers. To outside brokers, this was the holy grail. Getting access to the large customer base at Chase Manhattan Bank to offer portfolio management services. At the time, their ideal hire had to have 5-10 years experience, generate at least $250,000 in annual fees and commissions, and have at least $25 Million in assets under management. In my case I had none of that since I have worked at the bank over the prior 5 years and my series 7 license had expired and I would have to retake the dreaded 6 hour exam. So CMIS was not interested in hiring me. I was not the prototypical employee they were looking for. But I persisted. One of the senior loan officers, John Derasmo, said to me, “You’ve got tenacity.” Nobody ever told me that before but after thinking about it, he was right. Even though I considered myself shy, I never gave up when there was something I felt I needed to do.

Eventually, I wore them out. Hammond H., the CMIS branch manager of Jericho hired me, but with a litany of exceptions. “You are here on a trial period. You will have goals you have to make both on assets and revenue. You will be a 2nd Vice President and Not a Vice President like the rest of the reps.” Ok. “You will NOT make $125,000 plus bonus like the rest of the reps, you will make $50,000.” Ok. For me it was a big salary increase, I was only making $42,000 at the time. And my goal was to get a chance to prove myself.

Once I was fully licensed, and in my new position, I began to let everyone I knew at Chase know about my new role. Most had to refer to CMIS as part of their responsibilities, so they figured it might as well be Lou, someone we know and trust. Bankers were very protective of their customer relationships. Michael V., who ran small business lending for Chase’s Long Island region was my most important champion. Mike gave his loan officers strict instruction to refer to Lou any business customer that can use CMIS investment management services.

In the first year, with the help of my friends at Chase, I gathered $100 Million in assets. I was getting the large majority of the business being referred to CMIS on Long Island. I did not want to take a day of vacation or even leave my desk for lunch. That might cost me a big referral. Eventually, I was approached by my new manager, Joe F. Hammond H. was promoted to run the Park Avenue office of CMIS, and Joe F., a fellow advisor in the Jericho office was given the branch manager position. One of Joe’s first acts was to approach me to discuss the outsized number of referrals I was receiving. “I have 7 other advisors sitting on their hands while you get all the referrals from the bank. You need to partner up with one of the other advisors or I will notify the Chase Long Island region that you are not able to accept any additional referrals.”

It might be characterized as an embarrassment of riches. In the advisor business you never want to turn away potential clients, so rather than turn off the referral spigot, for a partner I picked who I thought was the most experienced and brightest of the advisors in my office. Jim V. de Walle was 8 years my senior. He had worked for a number of wirehouses including Shearson Lehman, EF Hutton and Smith Barney. He started his career on Wall Street after college as a runner for Arthur Levitt, Jr. while President of Shearson Hayden, Stone. Levitt would later become the longest tenured Chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Jim was the prototypical CMIS hire, experienced with about $25 Million in assets and generating about $250,000 a year in revenue. So when we partnered in 1995 we had a combined $125 Million in assets. A year later we had $200 Million. Business was great and we were living the dream. But as is so common in financial services, a big acquisition was coming and it was going to rock our boat.

Activist value investor Michael Price had accumulated a large position in Chase Manhattan Bank and was pushing the board to unlock value. Eventually this led to the merger with Chemical Bank. The management of the combined company was primarily from the Chemical Bank side, but they kept the Chase name. Initially I had high hopes that the combined entity would be a boon to CMIS. Back when I was a calling officer in Flushing, Queens, I called on many businesses that happened to be clients of Chemical Bank. While Chase had styled itself as a bank to the top tier of business and family wealth, Chemical focused on the blocking and tackling of small and middle market for business lending since the early 1970’s. Chemical Bank owned the market for C&I (Commercial and Industrial) lending in the NY Metro Area. Every Chemical Bank customer I seemed to call on was very happy with their relationship and had tremendous loyalty to Chemical Bank’s head of middle market lending, Frank Laurenso. Frank had been a fixture at Chemical Bank starting as a teller, and management trainee in 1963, going to Baruch at night earning his BBA and MBA. Frank eventually retired in 2013 after becoming an EVP at JPM Chase & Co.

Mike V., my champion at Chase had worked for Frank at Chemical Bank prior to joining Chase. I was able to meet with Frank for lunch at his office at 270 Park Avenue. I was hoping to explain what CMIS was doing and how it would nicely mesh with what he had built at Chemical. I reminded him that many of his early small business customers had grown into very large enterprises and some had become publicly traded on the stock market. The Estee Lauder company was a recent example. Wouldn’t it be great if Chase can get the investment banking fees rather a firm like Goldman Sachs who hadn’t had the long term relationship?

Very gracious, Frank explained that Chemical Bank had it’s way of doing things. They had the Private Bank who handled the clients with over $1 Million in investable net worth, and their branch program had junior advisors who handled the smaller customers. Chase too had a branch program, but CMIS filled the gap between the unsophisticated branch deposit customer and more wealthy client with significant investment experience. I left the meeting disappointed that the merger wasn’t going to be of benefit to CMIS, rather it was going to be cut out of the referral process. It was time for a major change.

When I returned to my CMIS office Jim and I began to strategize about our next move. Jim had grown tired of escaping the grasp of Sanford “Sandy” Weill and wanted to work for a regional rather than another wirehouse that Sandy would acquire. I had no interest in working for a large impersonal Wall Street firm. This led us to two well respected regional firms out of the Washington DC, and Baltimore area. We called Alex Brown & Son, and Legg Mason, Wood, Walker. Alex Brown’s NYC manager was happy to have us if we were willing to travel into Manhattan. Rich Levy, Legg Mason’s NYC manager was more proactive. He came out to Jericho and invited us to lunch. Ultimately, Rich’s response was the same as Alex Brown. “We would be happy to have you come into Manhattan or, if you get the rest of your colleagues to join you and we can open an office of 7 or 8 brokers, we would be interested.”

A week later Rich mailed us a follow up letter along with a Legg Mason annual report. On the navy blue cover Legg Mason listed its offices. Surprisingly, I saw “Jericho” on the list. I turned to Jim and said lets call information and get their office address. At CMIS our office was at One Jericho Plaza which was one of two office buildings in the complex. The 411 operator said, “Legg Mason Dorman & Wilson is at Two Jericho Plaza.” During our lunch break Jim and I walked across the parking lot to find the Dorman & Wilson office. We poked our heads in what looked like an empty 8 man office. The only person present was Laurie, the receptionist. We inquired if there was a manager. She said, “Ernie is here 2 days a week, the other days he is in our White Plains office.”

A few days later we met with Ernie D. Ernie explained that Legg Mason Dorman & Wilson had closed their appraisal department to focus on commercial mortgage underwriting and they had about twice as much space as they needed. His plan was to downsize when his lease was up in about 6 months. We told Ernie, hold on, we might be taking that space. When we returned to our office, we called Rich Levy to inform him, Legg Mason already has space on Long Island. A few days later we were hammering out the plans for Legg Mason Wood Walker’s first Long Island office.

The transition from Chase to Legg Mason went smoothly. Early 1997 was an exciting time for me personally as my daughter was born, and the “dot com” rally was the rage. Jim and I selected our top relationships which accounted for approximately $100 Million in assets to join us. The office was immediately profitable and we settled into what would be a rewarding experience.

By the time we opened the office, portfolio manager Bill Miller had beaten the S&P 500 for 7 consecutive years. At the time, only one other fund had done that, a Fidelity Select Fund, Home Finance which was a sector fund. Because of the great media coverage Bill was receiving, we were getting some unsolicited inquiries about the fund which is a rarity in retail brokerage. An old adage on Wall Street, “investment products are sold, not bought.”

Even though I didn’t work directly with Bill Miller, I did take advantage of every opportunity to learn from him. We had a number of internal conference calls where we could listen to Bill’s thoughts on the market as well as ask questions. At the Legg Mason President’s Council dinner I was able to secure a seat next to Bill, which for me was priceless. I realized that Bill was an anomaly to traditional Wall Street group think. And he surrounded himself with rigorous critical thinkers. Bill convinced Chip Mason to purchase Focus Capital Advisory to get access to author of Warren Buffet biographies, Robert Hagstrom. Robert managed the Focus Trust Mutual Fund which was later rebranded Legg Mason Focus Trust. Concentrated investing was a successful theme at both Legg Mason and Warren Buffet’s Berkshire Hathaway, as well at the theme of one of Robert’s books, The Warren Buffet Portfolio; Mastering the Power of the Focus Investment Strategy.

During the last innings of the dot com bubble, I was introduced to Edgar Wachenheim III, Greenhaven Associates Founder. At first Ed was willing to talk his book. He was buying housing stocks. He said they were going to make a lot of money on housing stocks and that he knew all the executives well. In 1999 I traded my own account to incredible gains, a credit to my trading expertise but also emblematic of how speculative and unstainable the market rally had become. I continued to make money trading internet stocks and wondered what Ed saw that the market and I didn’t see.

The market peaked by spring of 2000 and the market was rolling over and getting ugly. By 2001 the market was in a downtrend, and with historical perspective, the secular bull market that began under Ronald Regan in 1982 had clearly broken. We were now in a new market. The events of 9/11 further exacerbated an already weak market and economy. But despite the carnage among the former leaders like Dell, Cisco, and AOL-Time Warner, there were pockets of strength. Ed Wachenheim’s homebuilding stocks were taking off. The companies involved with mortgage finance, banks, and title insurance companies were doing well.

Following the events of 9/11 the capital goods analyst at Legg Mason, Barry B Bannister, began to write a research report exploring how the events of 9/11 would impact his universe of companies like John Deere, Caterpillar, Ingersol Rand, etc. The report which Barry began writing in October 2001, was published in April 2002. It was 84 pages and it opened my eyes to something that explain what was happening in the market and what would happen over the next 13 years.

THE INFLATION CYCLE OF 2002 TO 2015 https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/view/38112301/the-inflation-cycle-of-2002-to-2015-uhlmann-price-securities

So I was seeing the prior market leaders deflate, the market was now being led by companies that make or serve companies producing tangibles like housing, agricultural commodities, energy, and mining. These were “old economy” or “rustbelt” companies that didn’t receive any capital during the dot-com bull market.

Now they were getting pricing power because of supply shortages. Capital was flowing into build homes, mine gold, silver, and base metals, and drilling for oil & gas.

So finally I was understanding what Ed Wachenheim saw coming. What was left of the profits minted during the dot-com bubble were finding their way into “stuff.” But what Bannister pointed out, this wasn’t some fluke. This was a 14-17 year super cycle which had repeated for hundreds of years.

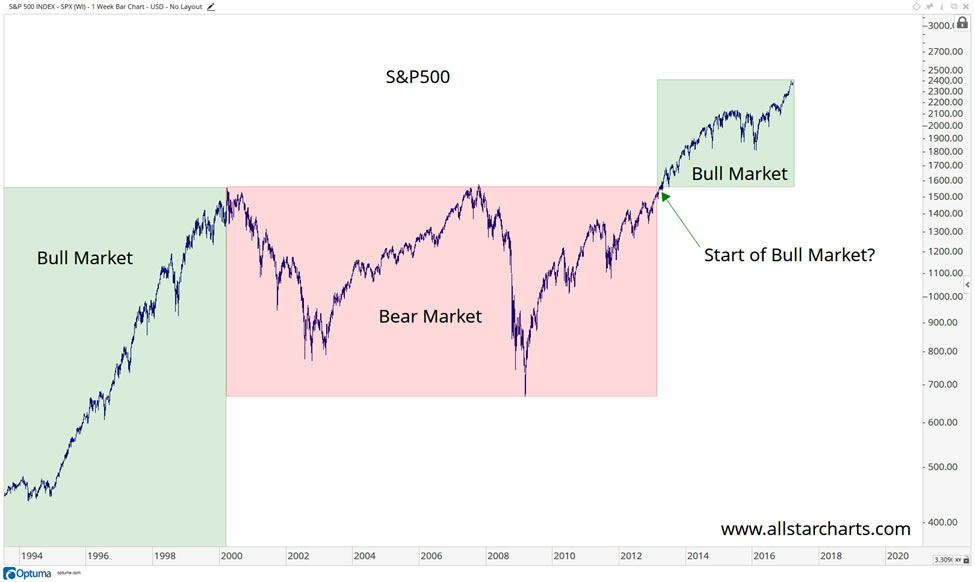

As I studied the prior super cycles, I realized they were also called secular bull and bear markets. As I understood the characteristics of these cycles it was almost like having a crystal ball in how to invest clients money.

I knew that the during the inflation cycle, which was essentially equivalent to a secular or long term bear market in stocks, would be defined by rising commodity prices and a stock market made no progress offering sub par returns. My goal during this period was to get “real returns” meaning that I was aiming for positive returns not correlated to the S&P 500. This wasn’t particularly easy since there were few products designed for such an environment. This was a period of great outperformance from the hedge fund community since many were pursing non S&P investments such as foreign currency speculation, international investing in bonds and stocks, commodity trading, risk arbitrage, etc.

While relegated to low expected returns, I knew that I had to conserve client’s capital during this bear market. But I also knew one day the cycle would flip, and a new secular bull market in stocks would be ushered in.

I figured that energy prices would need to peak and then fall due to technology breakthroughs and production increases. Also, political leadership needed to change from business hostile to business friendly. It is said that, “history doesn’t repeat itself but it rhymes.” As I studied the transition from Jimmy Carter to Ronald Reagan, I found a number of similarities to Jimmy Carter’s America to Barack Obama’s America. I expected another strong Ronald Reagan political character to emerge, but I didn’t see any in the political world.

During the summer of 2005 Jim and I heard talk that Chip Mason was going to swap the retail brokerage operation of Legg Mason to Citigroup Smith Barney for their mutual fund business. On paper this transaction made perfect sense. Chip had lamented that regulation and compliance costs continued to grow, so managing the already low margin retail brokerage business was getting more difficult and less rewarding. Chip loved the high margin asset management business that Legg Mason had built.

The problem that I saw was two fold. Legg Mason’s heritage was that of a brokerage sales force and a line of mutual funds that were unique in the industry. Also, Chip and Legg Mason had built a stellar reputation of integrity and trust. During Council meeting Chip would always remind the salesforce, “No chalk on your shoes.” The first time I heard this I turned to a colleague and asked what Chip meant. “He means stay away from the foul line. It was a baseball analogy, where many of our competitors would straddle that line, Chip wanted us to stay clear. Reputation was more important than the last dollar in profit.

Once I realized this transaction was more likely to happen I wrote Chip an email. Following stories Jim had told me about working for Sandy Weill during his career, and regular headlines disclosing more bad behavior out of Citigroup Smith Barney, I felt compelled to state the problem in culture between the two firms. I wrote Chip, “You always advised us, ‘no chalk on your shoes’ yet you are getting in bed with the guy who holds the keys to the chalk factory.”

Sandy Weill had previously lobbied the regulators, many of which like Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan and SEC Chairman Arthur Levitt III had worked for him, to drop Glass Steagal, a great depression era regulation that separated banking and investment businesses to protect the public. Jim witnessed Sandy’s decision making during his brokerage career. Early on during his career, Sandy earned the loyalty of his salesforce and he rewarded them with solid benefits. As Sandy acquired more and more competitors, he began to choose what was best for Sandy and his plans rather than his employee base. One of my friends and former Chase Manhattan colleague Michael DiPalma, a long term Citigroup employee lamented, “we used to be proud to be a Citigroup Banker, now it’s an embarrassment.” Michael had started at Citigroup in the early 1990’s while John Reed was running the bank. He witnessed what happened as Sandy’s culture took hold. While the legacy Citigroup employees didn’t like the work environment, Wall Street rewarded the stock. For the time being.

Faced with the prospect of becoming a Citigroup Smith Barney financial advisor, I began to think about our next move. Armed with the knowledge of what I gleaned from Bannister’s report and my additional research, I decided I wanted to work for a non-US institution, domiciled in a country that was natural resource and commodity rich. I picked up the phone and dialed RBC’s (Royal Bank of Canada) NYC office.

While RBC was the largest Canadian Bank, it’s US brokerage subsidiary was only about 2000 advisors, not much larger than Legg Mason. I figured that the culture would be a close fit. My initial pitch was for RBC to hire Jim and I and simply change the name on the door from Legg Mason to RBC Wealth Management. “We would be profitable from day one.” It took a while to convince RBC to open a Nassau County office, they had two on the east end in the Hamptons, but eventually Jim and I got our Jericho Plaza office established, back in One Jericho Plaza.

Once we landed at RBC, our loyal clients began to appreciate the stability and financial strength of the Canadian banking system in general and RBC in particular.

As I expected, whatever could go wrong, would go wrong in the secular bear market that began in 2000. While the financial crisis became full blown, my clients were mostly insulated from the volatility and panic.

More and more investment fund wholesalers approached me with absolute return strategy funds, designed to do what I had been doing since 2002. By 2010 I was thinking about developing my bull market strategy for the coming super cycle. Despite it’s stability and financial strength at the RBC holding company, the US brokerage subsidiary had little depth in management compared to what I had become accustomed to at Legg Mason. Instead of seasoned veterans who had worked for Chip for decades, I was dealing with junior administrators who were young and inflexible. I almost never was able to win a rational business argument that didn’t neatly fit policy. In fairness to RBC, this inflexibility wasn’t all RBC’s making, it was the regulations post financial crisis that always seemed to be protecting against the prior disaster that made doing business more and more difficult. But beyond the daily day to day, RBC lacked deep thinkers like Bill Miller, Robert Hagstrom and Barry Bannister. The former Legg Mason Capital Markets brain trust was included in the asset swap to Citi and was sold to Steifel Financial. Legg Mason advisors were prohibited from joining Stiefel.

Besides the increased regulations, the retail brokerage industry was under constant attack. Former brokers like Arthur Levitt were advising people to do it themselves, sending the message that advisors were unethical and their advice not worth their commissions or fees. The firms themselves would forever try to reduce the advisors split by adding convoluted compensation policies. John Bogle, visionary and founder of the largest index (unmanaged) fund complex also pushed the message advisors can’t add value.

Warren Buffett shared his investment advice given to his trustee when he’s gone: My advice to the trustee could not be more simple: Put 10% of the cash in short-term government bonds and 90% in a very low-cost S&P 500 index fund. (I suggest Vanguard’s. (VFINX)) I believe the trust’s long-term results from this policy will be superior to those attained by most investors — whether pension funds, institutions, or individuals — who employ high-fee managers.

As Bogle continuously preachs to anyone who would listen or read his books, the large majority of money managers will not beat a low expense index fund over time. And despite Bill Millers incredible record of beating Bogle’s Vanguard 500 for 15 consecutive years, it was impossible if you extended your investment horizon to your lifetime. In order to be truly successful in investing, you must approach it as a lifetime pursuit.

So how do I fashion a system that is effective, relatively fool proof, and durable? From my lessons learned at Legg Mason, the only real way to accumulate super wealth was through concentrated investment. Warren Buffett wouldn’t be synonymous with worlds greatest investor if he didn’t have his concentrated position in Coca-Cola. And manager that Legg Mason had acquired, Private Capital Management of Naples Florida, would be managing $65 Billion today if they continued to hold their Apple position from 1997 instead of the $600 million they currently manage.

I observed a number of people who had lifetime employment at a major public company accumulate incredible wealth relative to their earnings. The janitor who worked at Pfizer for 40 years retires with millions in Pfizer stock. It could have been Walmart, Coca-Cola, Johnson & Johnson, At&t, etc. It didn’t really matter which company so long as the time horizon was very long, and confidence to hold the shares was high.

I loved the mechanical strategy of the various Dogs of the Dow method that took emotion out of the buy/sell decision. But I also realized 5 or 10 stocks was too few for efficient diversification, (you need around 17 stocks) and you are only buying “value” stocks and not “growth” stocks.

So I was looking to create a strategy similar to an index fund. But where I and fellow advisors could add value above and beyond index fund investing. Where concentration was possible without taking on too much risk, but diversification added some stability. Also, one of the most important lessons I learned as an advisor is to develop a portfolio that clients could understand and have confidence in. The point at which the advisor adds value is when he or she keeps their clients in their investment strategy when normal and persistent human emotions take over. In other words, keep clients from selling low and buying high. This is the one thing Levitt, Buffett and Bogle can’t address when pushing the index approach, and yet this is the weakness in the human condition where individuals fail to meet their investment goals.

Bill Miller beat the S&P in part by dissecting the S&P index’s construction. It was a market weighted index. That means the largest companies by market capitalization are the biggest weight in the index. The S&P 500 doesn’t rebalance unless there are mergers and companies are removed by reorganization. So the best performing largest companies make up the largest percentage of the holdings. Active managers will typically “pare back” the top holdings once they become more than 5 or 10% of the invested capital. During the late 1990’s during the 15 year streak, Bill allowed AOL and Dell become 25% of his Legg Mason Value Trust.

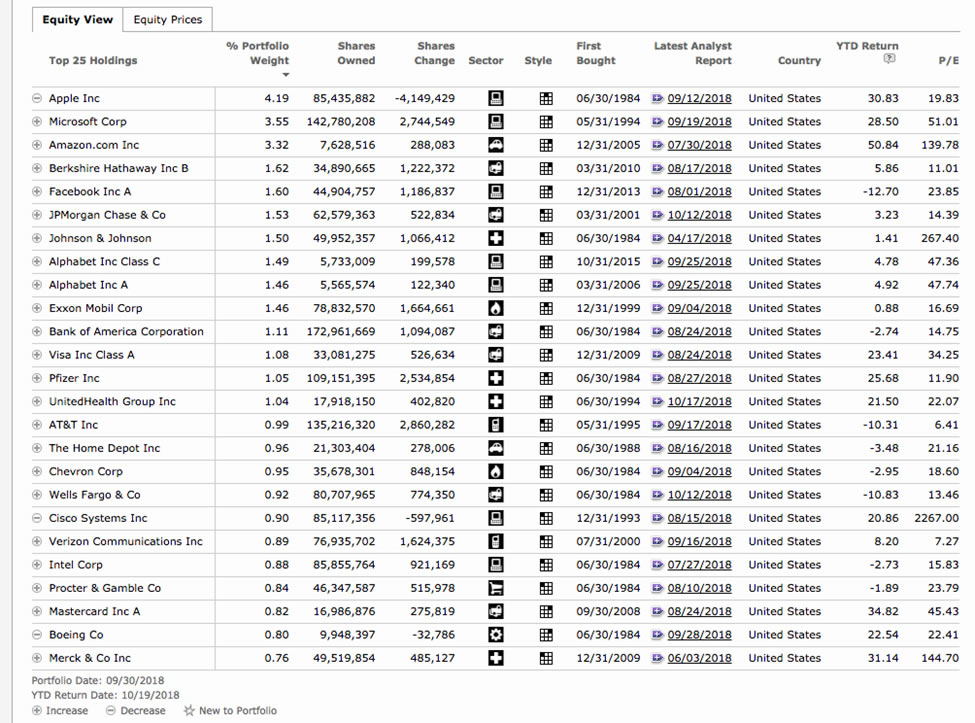

So I looked at the top 25 holdings of the Vanguard 500 fund:

First thing I noticed is every one of these companies are well known by most people, investors or not, so I figured this transparency of what you own may help clients stay invested during difficult market conditions. But I also noticed that the top company in the Index gets 4.19% of every new dollar invested while the bottom company only gets .76% of every new investment dollar. My first thought was, “Why not put 4% in each of the top 25 companies?” Next I thought, easy enough, let’s go back and test how this idea of buying the 25 largest companies equal weighted each January 1 would have done over the prior 20 years. As it turned out, from 1992 to 2012 this strategy returned about 1.5% per annum more than the S&P 500 index. Maybe I was on to something! I also tracked how the 25 would track the 500 Index. The R2 or correlation was .97 meaning that when the S&P 500 was up the 25 would be up, and if the S&P was down the 25 was down.

So I thought about it. These 25 super capitalization companies make up about a third of the index even though they only represent 5% of the 500. They cover a variety of the big industry groups, Technology, Consumer Products, Financials, Energy, Healthcare. Even though they are the largest, they tend to be cheaper vs their earnings (price earnings ratio) offering value. But they are also the most liquid of the market. Of the 25, 21 pay regular dividends, and depending on the list about 1/3 of those are dividend aristocrats meaning that they have raised their dividend in each of the past 25 years. What is really interesting is what happens when a new and exciting company comes on the list.

In the back tested group, I simply rebalanced and reconstituted the 25 each calendar year. So if a new company was now the 25th largest company, the 26th company got pushed off. That company was sold and the new company gets a 4% allocation. So if you think back about when Apple first appreciated onto the list, it was approximately a $100 Billion company. It would have received a 4% capital allocation. Today it’s more than $1 Trillion dollars. So assuming the other 24 stocks were unchanged, your 4% Apple investment was now approximately 40% of the portfolio. More recently, Amazon appreciated on, then off then on again and is now #2 behind Apple. Facebook appreciated on the list at approximately $40 per share, now trading around $150.

I was confident my supercap strategy was the right approach for the next secular bull market. Now I just needed the signal that the market has transitioned from secular bear to secular bull market. I pulled up the S&P 500 chart going back 20 years. I drew a line across the spring 2000 and 2007 S&P highs and waited.

The breakout happened in spring of 2013. At that point I spoke to all my clients to introduce my SuperCap25 strategy and began transitioning them to a fee arrangement instead of a commission relationship. With fee arrangement, I was aligning myself with the interest of the client and putting myself in a position to take the next leap in my career, becoming an Independent Registered Investment Advisor.

The SuperCap25 strategy worked. In 2013 I told my clients that the expected return should average 6-8% per year. Over the first 5 years with real money (as opposed to a hypothetical back test) we were far exceeding my expectations. In addition to great performance, the most important test was that market declines, clients did not call with concerns. Knowing the companies that you own is great comfort during market declines. All of my clients are familiar with the goods and services offered by the companies they are invested in. Who doesn’t know Google, Apple, Johnson & Johnson and Pfizer?

In the beginning of year Five, I launched my firm, Amore Ambro, LLC. Some of my clients loved the name, others thought it sounded like an Italian Restaurant, and others thought it was a joke. The key to investment success as I have discovered over my 33 year career is to remain nearly emotionless about money. Human emotions drive investment decisions, fear of missing out on great wealth, fear of losing money. When you make emotional decisions based on fear, you will lose. If you can keep yourself in a place of love, you can remain open to new opportunities and you will not be selling low and buying high.

My goal is to share my creation of the SuperCap25 with all investors and their trusted investment advisors. While in theory, anyone can use this simple strategy, only a few will succeed without the help of an investment professional. It’s not about math or numbers. It’s about fighting what humans are hard wired to do, fail to make rational decisions in times of fear. Science suggest only about 3% of us are able to remain unemotional in times of stress. This is why I believe the SuperCap25 strategy is ideal for investment advisors to introduce to their clients. Advisors can provide rational guidance in times of market turmoil. But they are also using a semi-passive strategy that requires less decision making in portfolio construction, research and asset allocation, all places where more variables are introduced and more opportunities to fail.

It is wonderful that investors have all the tools to invest their money. Robo advisors promise excellent long term returns. Just buy the S&P 500 index like Warren Buffett and John Bogle promote. The single issue they don’t discuss is why investors fail. And it’s simply that we are human. We need to rely on a trusted investment advisor when turmoil arises. And there will be recessions, market crashes, and political conflict. But through all of this, history proves that long term investing in high quality companies will build wealth, and without a trusted investment advisor, 97% of us will fail.

Amore Ambro, LLC is an Independent Registered Investment Advisor.